Zombies: History & Myth

Last year, to celebrate Halloween, I dedicated the entire month of October to a series about how to rethink vampires. This year, I'm going to do the same thing but for zombies – the much maligned, no-longer-particularly-scary low-tier undead common to RPGs. (Except I'll be tackling zombies in three parts, instead of four, since I wanted to highlight Cinder Edge last week)

You can check out the entire series for the month here – bookmark that page if you want to see the whole series as it comes out each week, or subscribe to the blog if you haven't already to make sure you do not miss any of the other parts!

Today, I'm going to explore the history of the zombie myth, including a couple of different things that zombies have stood for across the history of horror. Next week, I'll look at zombies in Dungeons & Dragons--including a homebrew product I adore--and talk about how to use these to ramp up the horror associated with them. And Week 3 will see me launch a zombie-themed product for Vaesen, like I did with vampires last year.

Zombie Interpretations

The Zombie Apocalypse

By far the most prevalent depiction of zombies in the modern world is that of the Zombie Apocalypse. Post-apocalyptic universes about zombies take off with media like 28 Days Later (2002), AMC's The Walking Dead (2010-2022), the comic series of the same name (2003-2019), and World War Z (a 2006 book turned 2013 blockbuster movie). It evolves in The Last of Us (a 2013 video game turned 2023-present TV show), where the zombies are created by a fungal infection... but are nevertheless recognizably zombie-esque.

According to Daniel Drezner, a Professor of Foreign Policy at Tufts, this modern, apocalyptic zombie represents the intersection of essentially two key modern fears: terrorism and pandemics. (Drezner lists three but I think they really boil down to two). Professor of Film Studies and leading scholar of the zombie genre, Kyle Bishop agrees, noting that the modern zombie era is a post-9/11 phenomenon--with over one third of all zombie films ever having been released since 2001.

The intersection of these fears is demonstrated mostly in the fear of the "zombie among us" – the classic moment of a zombie film when the protagonists learn that someone has been keeping a bite secret, and that now a zombie is inside their safe bunker. This is a fear stemming from concerns about infection, yes, which I'm sure we all can understand having survived COVID: who wasn't quarantining in 2020 and then lied their way into your bubble?

At the same time, post-9/11 fears around terrorism as something you simply cannot control permeate the culture. While exposure to disease might be something you can shape, being in the wrong place at the wrong time and becoming a victim of foreign or domestic terrorism, Al Qaeda or a mass shooting event, is something you cannot control at all... and it is something that governments seem to fail at stopping. The story of 28 Days Later, which is British, is not reacting to 9/11 specifically, but rather to the post-9/11 sense that the safe world order has collapsed, and it reflects a sort of terrorism-influenced commentary on hyper-individualism and being uncertain who you can trust.

In short, scholars talking about the modern rise in zombie apocalypse narratives focus on the apocalypse part: the entire world order collapsing, governments being proven incapable at handling the threat and being replaced (just think of the creation of FEDRA in The Last of Us) or dissolving completely, and not being able to trust the person next to you because they might be infected (with a virus or because they might secretly be a gun-nut poised to conduct the next mass shooting). That loss of trust and fear is certainly a focal point in 28 Days Later and in the foundational zombie movie of the modern genre (which is far more locally constrained and not a story of a global apocalypse), Night of the Living Dead, where both a child turns on her parent after being bitten and where, at the end, the black protagonist is shot by police after surviving the zombies, adding in a key racial component about police brutality and the dehumanization of black people in America.

The zombie craze passed its peak by 2016, as people got "zombie fatigue"--contributing to the Walking Dead's relative lack of popularity in its final seasons. The craze in zombie apocalypse stories is mirrored in the rise of parodies of that same genre: Shaun of the Dead (2004) reflects ideas around brain-dead consumerism and creates a template for other horror-comedies to parody, while Zombieland (2009) boils down surviving a zombie apocalypse into a series of trope-filled "rules." And so while the fears of pandemic and the collapse of the global world order are still salient in the present (perhaps even more than they were in the mid-2000s), the zombie apocalypse story built in reaction to those fears is commonplace and has lost an element of truly being fear-inspiring.

Like how I talked about the neutering of the vampire in last year's initial post, and the need to go back to the vampire's roots to make them effective creatures of horror and social commentary, I'm going to argue for the same thing for zombies. We need to find an earlier meaning for zombies if we want them to be thematically-relevant and psychologically-frightening.

The Earlier Zombie

Unlike with vampires, there's no one root "zombie". The word comes from Africa and from Haitian Creole. Other rotting undead corpses, like the Norse draugr or the Arabic ghul, certainly have their own folkloric trajectories and allegorical meanings. There's so many types of zombie creations that most media refuse to call them zombies: 28 Days Later calls them "the infected," the archetypical zombie films from George Romero uses "ghouls," The Walking Dead uses "walkers," and even Zombieland cracks jokes about calling them anything other than "zombies."

So instead of trying to focus on any of the more specific folklore etymologies of zombie-adjacent creatures, I'm going to focus on one particular earlier strand of movie zombie-ism that I think would be effective to a modern audience: the zombie of capitalism.

Zombies in all their forms reflect a loss of individualism. If you're in the apocalyptic horde, you've lost your sense of self. And what is more grinding than the oppressive forces of capitalist sameness? Individual character of artisanal goods are transformed into mass-produced clones. Workers move from being responsible for every part of manufacturing to assembly-line tools, which can then be replaced by inhuman robots doing the same work.

It is this social commentary that is the major pre-apocalyptic strain of zombie stories. Jeremy Dauber, in American Scary, writes about the introduction of the zombie to American stories in 1932, when William Seabrook writes about Haitian necromancy turning "'the soulless human corpse' into... 'a slave' called the zombie." Daniel Drezner notes that the zombie's more original form was a commentary on slavery, a symbolic thread echoed in a New York Times column about the history of zombie-ism.

Night of the Living Dead's 1978 sequel, Dawn of the Dead, shows the end-stage form of this story, where the zombies shamble around a shopping mall in a grotesque imitation of their pre-undeath behavior. The Night of the Living Dead's racial commentary also provides a link to the dehumanization of black people in America, also linking back to earlier depictions of zombies as slaves. In 28 Days Later, as we transition into the modern apocalyptic zombie, we're still seeing links to racial exploitation as Mailer--the one black soldier--is chained up and forced to do labor once he is infected, while Selena (a black woman) faces sexual enslavement; both common dynamics in real slavery. The earliest film in the zombie genre, White Zombie (1932), combines these racial and capitalist fears as well, when a white woman visiting Haiti is turned into a zombie by a plantation owner whose entire workforce is undead.

While these racial tensions are also certainly ripe for exploration, I'm certainly not the person to run a game exploring that. However, if racial dehumanization and slavery is one part of the early zombie allegory, the capitalist pressures that led to such practices are the other part. Zombies do not need to be fed or paid--it is the same motivating force behind companies shifting to using AI tools for customer service and automation for manufacturing: a one time investment that lets you then cut your payroll.

And so as we all witness the horrors of late-stage capitalism, of the mindless crush of big business against individuality, I think that the opportunity for a very different allegorical zombie is ripe for use. Plus, these zombies do not need to be a global apocalypse: you can tell much smaller-scale stories about zombies-under-capitalism than you can about zombies-as-disease.

Defining Our Zombies

So we know what our zombies are going to symbolize: the crushing weight of capitalism, something that works for a modern audience and that also has a long allegorical history in the zombie medium. But there's lots of different depictions of zombies so sort through in order to figure out how our zombies should behave.

Fast vs Slow

One of the main distinctions in zombie media, beyond what the zombies are allegories for, is whether the zombies are "fast"--literally moving rapidly, capable of running or climbing--or "slow" and shambling.

The Fast Zombie shows up occasionally, mostly in Italian films and (arguably--literally, there's people who argue whether these count as fast or slow) in Romero's early work, until 2002. 28 Days Later is the work that truly catapults them into popularity, where they'll be used in other apocalyptic zombie media like World War Z and The Last of Us.

This works well for the zombies-as-apocalypse story. If your story is about how governments are unequipped to deal with terrorism, the horror of being suddenly overwhelmed certainly fits. More importantly, pandemics spread fast. In fact, the dividing line seems to be that fast zombies appear where the zombies are not fully dead, but rather infected somehow (true in The Last of Us, 28 Days Later, and World War Z). Fast zombies are a part of the zombies-as-disease genre. But I think that there is a reason that fast zombies are a pretty new innovation to the genre--they don't fit the allegories of capitalism and slavery.

On the other hand, the slow zombie has a much more storied past. Zombies shamble. Even The Walking Dead, despite being an apocalyptic show, has slow zombies. Simon Pegg, who wrote and stars in 2004's parody zombie movie, Shaun of the Dead, is a strong believer in the slow zombie. He argues that zombies represent death, and death is creeping. Death can be postponed if you're clever and try hard enough, but it will eventually get you.

This argument is compelling, but I think zombies represent more than just death. How many service workers are high-energy at the end of the day? Does working a job under capitalism leave time for anyone in the working class to feel well-rested? No – that is one of the hallmarks of being overworked. And so having high-energy zombies sprinting around everywhere misses the capitalism's oppressed laborers allegory; the zombies are forced into drudgery, and they stumble, sleep-deprived, from one thing to another.

On the other hand, zombies can still use tools, as they do in Romero's works. If they couldn't, they'd lose their utility as workers. So a zombie can be taught--slowly and painfully, probably--to use a sword or turn a wheel, though it will always be clumsy.

The Bite, Brains, and Contagion

The hallmark of the modern zombie is the bite or other method of spreading illness. In The Walking Dead and other stories where zombie-ism spreads like a plague, being bitten is the undeath sentence. There might be other ways, especially for the first outbreak to occur: something spontaneous animating existing corpses like in the Walking Dead, some sort of initial disease pathogenesis like in The Last of Us or World War Z, or a biochemical weapon like in Planet Terror. In 28 Days Later, zombie-ism is an illness in bodily fluids, and so exposure to blood spreads the disease faster than a bite; in The Last of Us, you need to get close enough that fungal spores infect you.

This is again a useful device in stories of zombies-as-pandemic, but is less relevant in stories about zombies-as-capitalism. In White Zombie, it is through drinking a potion and the use of magic that spawns a zombie--zombies themselves cannot create new zombies. In fact, I think this is critical to the zombie-as-capitalism allegory: you need a capitalist for that story to work, and so you can't have the zombies spread without some sort of "boss" figure.

In fact, the zombie hunger for brains is a product of Romero's work before its mass adoption. Early capitalist zombies are exploited workers who have lost their humanity and their souls, or (more accurately) had them captured, rather than being the threat themselves. The zombies might kill you, yes, but they're being marshalled by someone. They are not innately driven by a supernatural hunger to kill you, even though they cannot be reasoned with.

So we're going to keep that: our zombies do not spread through bites, and they do not have some innate hunger. We'll leave that for the term Romero uses for his own zombies: ghouls, and we'll keep our zombies as the marshalled forces of a necromancer.

Killing a Zombie

Vampires can be killed with a stake through the heart (and simultaneous decapitation, according to Bram Stoker). Werewolves die to a silver bullet. What kills a zombie?

According to Romero, the Walking Dead, and a lot of other modern movies, zombies die when you destroy their brains. They'll survive more minor wounds and keep coming, but destroying their brain works. Fire is another way to defeat a zombie in most of these media.

In 28 Days Later and other forms of "infected-but-not-fully-dead" apocalypse zombies, anything that can kill a human can kill a zombie if you put enough power into it, but that they'll charge through pain or fear. Anything that outright kills a person works, but anything short of bringing death won't.

In our more capitalism-focused works like White Zombie, however, it is killing the boss that frees the enthralled zombies from their zombie-ism. In some earlier Haitian folklore, the way to "rescue" a zombie--to kill them and let them move on to the afterlife--is by stuffing their mouths with salt. But the point of both of these is that it should be really hard to kill a zombie: they're being forced to work and work and work, animated by a particularly hard-to-kill spirit of the capitalist ethic.

And genuinely, I think that this is something that a lot of RPGs fail to capture in the interest of "game balance"--and it is one of the earliest fixes I put in for zombies in my world. You shouldn't be able to kill a zombie outright using normal means. A D&D Zombie's Relentless Endurance trait, letting them survive the first should-be-killing blow is a gesture at their immortality and superhuman resistance to harm, but it is not enough. You shouldn't be able to kill a zombie by pouring on the damage fast enough.

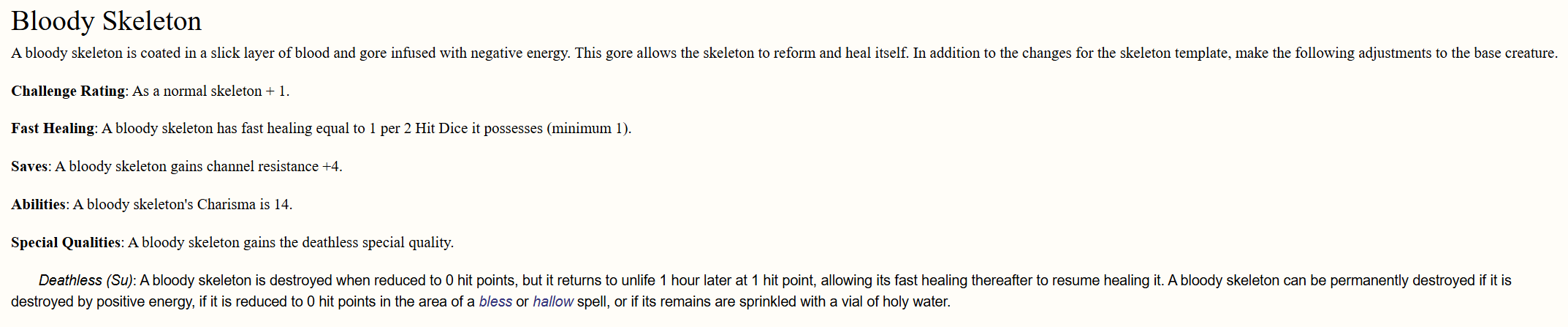

I'll talk more about this next week when I discuss adapting D&D Zombies specifically, but I'll start by saying that Pathfinder's Bloody Skeletons are a good start on how to really make a mundane sort of undead feel genuinely scary and unkillable--as a shambling zombie should be.

Conclusion

So, overall, here's our image of a zombie that heralds back to earlier depictions of the shambling undead. We'll be using this to design TTRPG zombies going forward and to evaluate whether existing TTRPG zombies fit our needs. This is not the only depiction of zombies, but if we're trying to move towards something that is useful to us, where we're aware of the "zombie apocalypse burnout" factor, where we're trying to tell smaller-scale stories that our PCs can engage with without it becomes the whole campaign, then these are the types of zombies we're going to be using for the purposes of this series on the blog.

1) The zombie threat represents the pressures and demands of capitalism's worst impulses for seeking profit at the expense of humanity. Our zombies also can be local and focused, and so are not necessarily a world-ending cataclysmic threat.

2) Zombies move slow: they shamble rather than run. They can use tools and weapons, though they do so clumsily. A zombie catches you because they never need to stop to sleep or to catch their breath, not because they can outpace you.

3) Zombie-ism is not contagious, and one zombie cannot make a second zombie unless somehow specially empowered to do so. Zombies are created by a necromancer or other magic source, and this source has control over them. There's no zombie plague.

4) Zombies are practically impossible to kill, unless you kill the necromancer who raised them or you have magic on your side (or maybe if you conduct a certain ritual). But simply piling on damage can only work to stun them temporarily.

I hope you all enjoyed this breakdown! Next week, we'll be taking these four factors to look at zombies in Dungeons & Dragons--both what's already been published and in a few selected homebrew works!