The Power of Bones: History & Myth

Part of the Magical Practices Project

Part of the Osteomancy series

This article is going to kick off a big project and a short series that will be part of that project. Let's start with the big one: exploring real-world 'magical' practices (click here for the full archives of that project). The short series is all about one of these practices: the casting of bones, also called osteomancy (click here for that series specifically). I'm not necessarily dedicating every upcoming post to these series, but a lot of them will be.

My inspiration for this project is an area where I think a lot of RPGs fall short. There are a bunch of different 'methods' of doing divine spellcasting because of the variety of gods. The world where my personal games take place has four unique pantheons, and possibly five if you count a budding heresy as having real gods, with each having a different flavor as to what constitutes 'good behavior'.

Arcane magic, on the other hand, tends to all feel somewhat similar. There are some differences in lore: wizards, for example, study magic until they're able to understand it; Warlocks draw power from a patron; sorcerers have an innate casting ability in their blood; bards use music and storytelling. In practice, however, these tend to manifest as minor roleplaying differences. Not every wizard character is a bearded scholar, for example; and the non-scholar wizard and the non-scholar sorcerer tend to play pretty similarly at the table. Unless we're going to tie backstory to class more significantly (which I don't think we should), it leaves the GM with fewer tools to make arcane practitioners feel different than they do even between two different clerics–people of the same class--who have chosen different gods.

This is at odds with the way 'magic' has functioned in the real world. There are countless different expressions of magic in history, from voodoo to tarot. Where is that sort of historical inspiration? How can that wide variety of practices be unified into an existing structure? What lessons can we take to make magic in our homebrew worlds feel more varied and unique?

This also serves a secondary purpose for me. I am in the slow process of moving away from D&D and migrating to a homebrewed system – more details to come in future articles, I promise, once everything is a little more fleshed out. As I build out rules that will represent the more varied magic system of my home game world, I want to make sure that I am keeping the lessons of history in that system and trying to reflect a large variety of types of arcane magic.

With that long introduction out of the way, this post is going to dig into one such alternative style of magic: casting bones, called osteomancy. This week's post is going to focus on the history behind that style of magic, and the next few weeks will work on building out usable homebrew structures based on history.

Dice Rolling: Divination Using Bones in Europe

When I first started exploring the concept of "throwing bones" as a form of magic, I was imagining a scene from a book I had once read set during the Middle Ages, where a Viking "rolled the bones" to determine whether it was an appropriate time to attack. However, as I read more academic work, it quickly became apparent that the bones themselves were not highly important by themselves to the European tradition.

Fritz Graf, an archeologist & professor at Ohio State University, wrote about the broader trend of dice-rolling oracles in the ancient Mediterranean in an article that I've linked below for anyone interested. The importance is not so much on the bones themselves but on the results being rolled. Bones would be carved into four sides, with numbers on each face, and then rolled to determine the portent being given. This bone-dice rolling is called "astragolomancy." The bone elements of astragolomancy are so unimportant in the Greco-European tradition that imitations of bone "in bronze, wood, or ivory" were seen to be just as credible as bones themselves.

Graf lays out the process used in astragolomancy. Five dice are thrown, and then the sum--or the order of the rolls--is compared to a set text or a human interpreter. Graf also provides a translated copy of one of these set texts; one sample roll is "Zeus will give good thinking to your mind... he will grant happiness to your work," for rolling all ones.

This is similar to the ancient Roman historian, Tacitus, in his account of the people of Germany. That practice, called cleromancy, is a more general mode of generating randomness as a way of attempting to divine the future. Tacitus, in his Germania, writes that:

"To divination and casting of lots, they pay attention beyond any other people. Their method of casting lots is a simple one: they cut a branch from a fruit-bearing tree and divide it into small pieces which they mark with certain distinctive signs and scatter at random onto a white cloth. Then, the priest of the community if the lots are consulted publicly, or the father of the family if it is done privately, after invoking the gods and with eyes raised to heaven, picks up three pieces, one at a time, and interprets them according to the signs previously marked upon them."

Again, the emphasis here is on the markings already on the items being cast. The items themselves are less important than the relevant markings carved into them. Similar reports exist in the Hervarar saga, indicating that the casting of lots as a mode of divination did persist into the Viking age, but the emphasis there is also upon the markings on the items rather than the items themselves.

Between these two historical roots (Greek astragolomancy and German cleromancy), it seems that this sort of number or symbol-driven scrying is the historical inspiration for my historical fiction-based recollection of Vikings 'casting the bones' to determine an omen. It is the symbols that are significant in the prediction being made, whether those symbols are numbers or runes with specific meanings.

Burning Bones: Scapulimancy in China and the Americas

I went further afield in researching magical uses of bones for divination purposes, beyond the historical fiction Viking-inspired image I had in my head of 'throwing bones.' That said, I did want to stick with the idea of bones as a form of divination about the future, as that was an element that I liked from the astragolomancy tradition and wanted to incorporate into my worldbuilding – not to mention something that D&D's magic struggles with (just look at the relative lack of divination spells compared to most other spell schools). Even when D&D has divination, it tends to either be very meta (storing dice rolls a la the Divination Wizard's Portent ability) or very up to GM discretion ('ask the DM a question' style of abilities, a la the Divination or Augury spell). More on this in a later week, when I talk about using history to make better divination magic for a TTRPG.

This wider exploration led me to the tradition of "scapulimancy," which is where bones are ceremonially burned, and the cracks that emerge in the bones provide the source of information for the caster to use when foretelling the future. In this sort of divination, a large bone (typically an ox's shoulder bone) would have small pits drilled into it and then a statement would be carved onto the bone. The statement would be an assertion like "it will rain within the present moon." Then, a hot rod would be inserted into those small pits, heating the bone until it cracked. The pattern of the cracks would then either confirm or reject the statement that had been carved into the bone.

Scholars of scapulimancy note that this style of divination of the future was widespread throughout the ancient Eastern world, from Japan to Arabia. Interestingly, however, it also appears in the Americas. The "Naskapi, an Algonquian-speaking tribe who lived in the tundra lands of Canada’s Labrador Peninsula.... [used the] pattern of cracks in a caribou shoulder blade." The Eastern Cree also used scapulimancy of caribou shoulders.

While I have not been able to find that much academic research into European scapulimancy, one published dissertation does reveal that some version of the practice was in use in Flanders--part of modern-day Belgium--around the 12th and 13th centuries. The medieval scholar Gerald of Wales wrote: "A strange habit of these Flemings is that they boil the right shoulder blades of rams, but not roast them, strip off all the meat and, by examining them, foretell the future and reveal the secrets of events long past." However, it does not necessarily seem from the sources that the heading of the bones was necessary for the Flemish practice, and the remark that it is a strange habit suggests that the practice was not common elsewhere in Europe.

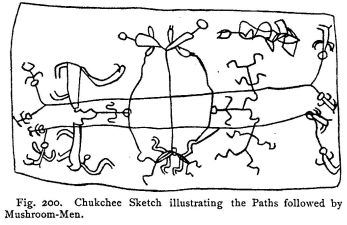

That said, the specific details on how to read the cracks in a bone are harder to come by. The main source that I could find actually detailing the process of scapulimancy, rather than just reporting on the cultural impacts of the practice, is from a 1904 Russian work about a Siberian group called the Chuckchee.

In this, the author, Bogoras, reports that the Chuckchee method of scapulimancy works as follows:

"If there is produced only one vertical line, it is a favourable indication; but if this line is short, or, on the contrary, if it reaches the very edge of the bone, the indications are unfavourable. Should the bone burn too quickly, it is likewise unfavourable. The small crosslines not reaching up to the principal crack, when in the upper region, foretell only news of something; while the longer lines, crossing the principal crack, foretell the arrival of the thing. A large cross zigzag line foretells greatness of the thing which will come. For instance, a detached crossline from the “mountain” may signify news about wild reindeer; a longer line, the coming of wild reindeer; and a zigzag line, the abundance of the wild reindeer; etc."

While this is certainly useful, I am sure that the reading of the bones is likely to vary from culture to culture. I wish there were more resources available concerning, for example, how the emperors of Shang China read their prophecies, rather than just that they did.

Throwing Bones: Osteomancy in Africa

The image that I originally had about Vikings, of someone throwing a pile of bones onto a mat and making prophecy based on the locations of those bones, was realized in southern Africa. The Phansi Museum, located in South Africa, has an excellent resource about the history of "bone throwing" in Bantu-speaking southern African cultures.

Bone throwing in southern African cultures involves the casters, called sangomas or inyangas in Bantu, picking objects that they find significant – often assorted small bones, along with dice, stones, coins, or other small objects. Often, specific meanings are connected to specific objects in the set of bones. For example, a hyena bone might be representative of a thief, and so if the hyena bone falls in a particular place, it would suggest that a theft is likely or unlikely to occur.

The Phansi Museum reports that one primary method for interpreting the bones is the "use [of] four principal bones which represent family and a number of supplementary bones each representing a part of society. In a bone throwing ritual the four principal bones must be used and supported by supplementary bones grouped in pairs."

As an example, if a baboon bone falls facing someone, they are favored. So, if death is indicated by the ant-bear bone pointing at someone, and the baboon also faces that person, then they will be close to death but it is possible to find a cure. The meanings combine. The Phansi Museum goes on to discuss several other key patterns observed in the interpretation of bones, but it is clear that positioning and facing are important – who the bone points at, for example, determines the prophetic role that they will play.

Key Elements

We now have three historical roots for some sort of bone-derived fortune-telling magic. These vary in practice, cultural context, method and rigidity of interpretation (from Greek written rules to our potentially nebulous Chinese scapulimancy practices), and even the importance of bones. However, there are two key unifying takeaways from our research that we can use to inform our TTRPG campaigns.

The first takeaway is the idea of randomness. When you heat a bone, the crack is a mostly random pattern. Dice rolling in our Greco-European tradition is random. Tossing bones onto a mat leads to a random pattern of how the bones will fall.

However, scholars criticize the notion that this randomness serves no historical value, nor was it somehow "primitive." Fritz Graf, in his discussion of Greek dice oracles, says that in cultures that believed in the possibility of learning the future from the gods, randomization served as a necessary and even intentional step to give room for higher powers to act and convey their messages. The 1950s Yale anthropologist, Omar Khayyam Moore, goes a step further and argues that randomness served as a sophisticated method to avoid unconscious bias. Using the randomness of bone cracks to guide whether you continue to hunt in one area or to move on can be a method of avoiding overhunting one area, and relying on it can also prevent unconscious bias or social pressure from dominating a decision.

This is a great consideration to keep in mind when building out a TTRPG world. TTRPGs also rely on randomness, so we should embrace the role that randomness plays in both games and divination, rather than trying to build a system that would remove an element of randomness for the sake of "prophetic accuracy." Even in a system where we want our magic to definitively exist, rather than being up for debate, prophecy should still have an element of randomness to it.

Our second key lesson is about the power – or lack thereof – of the bones themselves. In two of our cultural traditions, African osteomancy and European astragolomancy, other objects can be just as relevant as the bones themselves. Coins, replicas made from wood, and dominos variously can serve the same role as a bone. It is only in the practice of scapulimancy that the bones themselves matter.

One potential reason for this is because of the cultural context where these practices evolved. Arwen Johns, who was our source on the Eastern Cree and Naskapi Innu practice of scapulimancy, argues that primarily hunting-based cultures often develop an understanding of animals as "other-than-human persons," while more agricultural societies – particularly Western cultures – see animals as objects. This fits some of our examples as a root for the differing roles of bones in our bone-based divinations, as most Bantu-speaking cultures practicing bone-throwing are historically agricultural societies. According to Johns, this development of animals as persons imbues them with more power, giving their bones a unique power more significant than, say, a coin, which can be more easily fit in as an equal source of information in a society that sees animals as mere objects.

This theory breaks down, though, when you consider that many Bantu-speaking cultures had a traditional animist religion before their contact with Islam and Christianity, meaning that they placed high importance on animal spirits even without being hunters, and yet allowed other objects to be incorporated into their prophecy. Similarly, Shang China was an agricultural society, and yet was focused on ox shoulder bones and turtle shells for their scapulimancy, rather than adopting other objects into the list of acceptable divination tools.

To me, it seems more that this is a matter of convenience or necessity. Scapulimancy relies on the cracking of bones as the mode of fortune-telling, and so only really works with bones. A wood imitation of a shoulder bone, for example, would just catch flame. Rolling dice or throwing bones do not necessarily need to be bones; any carved, small object could act as a die, and any comparably-sized object could serve the same positional function as a bone.

Still, I do like the logical idea that in societies with strong connections and respect for animals-as-nonhuman-person (such as hunter-based societies), bones would be more important to their ritual than in societies that see animals as objects.

In future articles, we'll be taking these two key elements and these varied practices as our guiding principles for developing homebrew content around the theme of bone magic. Be sure to subscribe to receive new articles delivered to your inbox and make sure to not miss a new post! Thank you for your support.